Sep 06, 2022

Of all the ideas that I wish had made it into the current edition of Conceptual Labor yet somehow did not, Calm Technology is the first one I think of. It really feels like a serious omission (which perhaps I can correct in later editions) given its various connections to the Theory and me personally. One of its major contemporary proponents, Amber Case, is one of my closest friends. Which is why when you go to calmtech.com, you are visiting a website I rebuilt according to the Calm principles Amber requested. At the other end of its history we have John Seely Brown, who, with Mark Weiser, co-authored the establishing papers on Calm Technology. Brown’s research elsewhere provided valuable insights and background to some of my favorite parts of the Theory.

What is Calm Technology?

Calm Technology is an approach to design based on the following principles:

Principles of Calm Technology

A Calm Technology should:

-

Require the smallest possible amount of attention

-

Inform and create calm

-

Make use of peripheral attention

-

Amplify the best of technology and the best of humanity

-

Communicate, but doesn’t need to speak

-

Work even when it fails

Like the Theory, these principles each have sub-concepts.

The point of these principles is to create technologies – whether physical objects or digital interfaces – that work effectively for the humans rather than the other way around.

Calm Technology and Conceptual Labor both focus on the experience of individuals at work. A Calm Technology isn’t just something that looks nice, or is quiet, or easy to use; it’s one that creates what Brown and Weiser called a “fundamentally encalming experience” as a person uses it. The calmness of the experience hinges on how a technology engages the user’s attention. Weiser and Brown say

Calm technology engages both the center and the periphery of our attention, and in fact moves back and forth between the two. 1

Talking about Calm Technology, then, means talking about the process of engaging with a technology. The use of a truly Calm technology is a dialogue that starts before we pick up the tool, and takes into account how we will put it back down. I think this is what makes translating Calm Technology into conceptual labor terms an interesting and useful exercise, because the Theory gives us tools to deeply articulate this dialgoue.

In the Theory, talking about the experience of work means we’re talking about labor. What aspects of labor we pay attention to and why are also central concerns of the Theory, which we describe using models comprised of actors, work, and context. Anyone familair with the Theory should have no trouble describing the movement of attention in Calm Technology in these terms. But I think this compatibility indicates deeper symmetries between the two theories.

Making conceptual labor more comfortable and enjoyable

Calm Technology theory brings the general patterns of the Theory to bear on concrete problems and real-world experiences of people and their work. Probably the most important shared pattern is Principle III of Calm Technology. Taken with its subconcepts, it formalizes the assertion about the movement of attention.

- Technology should make use of the periphery

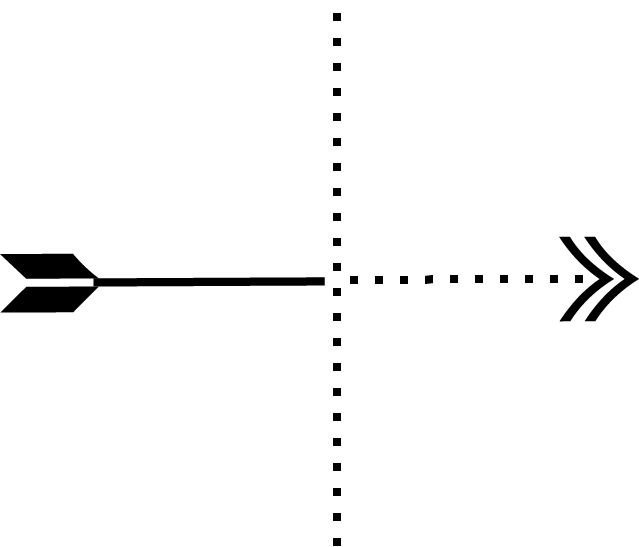

- A calm technology will move easily from the periphery of our attention, to the center, and back.

- The periphery is informing without overburdening.

It’s easy to align the idea of the periphery with conceptual labor’s ideas of context or medium, but we know that the periphery is important because it has a dynamic relationship with us as actors. Weiser and Brown’s 1995 paper on Calm Tech describes this relationship this way:

We use “periphery” to name what we are attuned to without attending to explicitly. Ordinarily when driving our attention is centered on the road, the radio, our passenger, but not the noise of the engine. But an unusual noise is noticed immediately, showing that we were attuned to the noise in the periphery, and could come quickly to attend to it. 2

This depicts a process of moving from a conventional narrative (where our peripheral knowledge remains unquestioned) to one that needs to be re-examined or reassembled; in other words, it describes conceptual labor. (It even uses an example that I explored from an entirely different source in the Theory.) A technology that “move[s] easily from the periphery of our attention, to the center, and back,” is one that initiates and exits the process of conceptual labor smoothly. This is the “fundamentally encalming” experience that Calm Technology seeks to create.

What it means to be Fundamentally Encalming

From a conceptual labor standpoint, what Weiser and Brown call “fundamentally encalming” sounds like the relief of returning to the conventional narrative after a bout of conceptual labor. A relief at returning to a state where you can let your periphery – your context, your understanding of the medium in which you work, and all your working definitions of the components of your models – be what it is and, well, “just do the work.” But it’s more complex than that; remember Calm Technology is focused on the movement of attention from the periphery and back, not checking the box of “I no longer notice this technology” and calling it done.

We have go deeper than “a conventional narrative is calm, conceptual labor is not calm.” Calm Technology principles describe a fluid and satisfactory process of conceptual labor. One in which the inevitable modification of our conventional narrative or our working models in the process of labor is swift and linear, or at least where it concerns the technology that facilitates it.

This fits nicely with fundamental fixed scale of conceptual labor, and the tenet that introduced it, Tenet 7:

- Conceptual labor tends towards abstraction but is rooted in specifics

The ‘periphery’ in Calm Technology theory is the abstract space of our assumptions. It’s the part of our model that we don’t have to worry about – either a known component, or better yet, an unexamined aspect of our context or medium.

A Calm technology moves from the abstract space of the periphery to the specific experience of our focused attention and use, and then back again, without much fuss. It traverses the fundamental fixed scale, from here (our focus) to there (the periphery).

Case elaborated on this point on our conversations:

I think there’s a deeper feeling I get – the fundamentally encalming encounter with work is that things have been thought of and considered beforehand. And that itself is conceptual labor. That part is invisible when you have a good experience or a complete experience.

I think this gives us a more human way of thinking about technology. One in which technology is a physical expression of how we model work, rather than a monolithic fact of the world that our models have to bend over backwards to accommodate. Weiser’s concept of ubiquitous computing (or ubicomp) envisioned such a world. The terms of conceptual labor can help elaborate many of the ideas that came out of it (and are active in our time of smartphones and IoT devices) – the more technology seems to be ubiquitous the more we can think of it as a context rather than an actor in our models which use it to do work. Of course, the criticisms of ubicomp – mainly based in privacy, transparency, and environmental concerns – bring us back to the reality in which technology remains a flawed and present actor. There are hazards, it seems, to fully relegating work to the periphery. We need to continuously examine and justify what we pay attention to, and what we ignore.

The periphery is very hospitable to the assumptions and unexamined models of the world that form the starting point of the stories we tell ourselves about work. It’s important to remember that, even though much of conceptual labor consists of examining the unexamined mental background of the Periphery, it’s home to much of our wisdom. Calm Technology knows this – the value that it places on the use of peripheral knowledge aligns with my assertions that the Theory and Conceptual Labor Analysis should not take the place of less purely-rational methods of labor. Conceptual labor is hard because, during the process, we cannot rely on the full powers of our peripheral knowledge and strategies. Likewise, making a Calm technology is hard because it must be designed to empower these esoteric yet valuable methods of making sense of the world via our peripherial awareness, without drawing too much attention to those methods. Calm Technology, like conceptual labor, is ultimately about the experience of work.

Further thoughts

This means that if we are going to use either of these ideas to measure work in some way, to describe it in some way that we can evaluate it, we must describe the experience in whole rather than its discrete components. I’ve started to write in this direction, using conceptual labor concepts to articulate ideas about Calmnness, but I’d like to talk to Amber more first, as she’s directly involved in such an effort as a professional. So check back for more posts on Calm Tech and Conceptual Labor.